Fixed Supply, False Security: Why Bitcoin and Gold Fail as Reliable Monetary Anchors

Understanding these monetary principles places you beyond the level of insight once held by the Fed’s highest-ranking officials.

“Gold is a currency. It is still by all evidences the premier currency where no fiat currency, including the dollar, can match it.”

Alan Greenspan, 13th chairman of the Federal Reserve

Nowadays, only stupid armchair economists and outright idiots seriously advocate for a return to the gold standard or the adoption of a Bitcoin-based currency. These proposals reveal a fundamental misunderstanding of monetary economics and an unwarranted nostalgia for rigid monetary regimes. Fixed-supply currencies, whether anchored in gold or algorithmically limited like Bitcoin, fail to account for the critical need for monetary elasticity in modern economies.

Proponents often argue that such regimes impose discipline on monetary authorities and protect against inflation. Yet this discipline is illusory: by eliminating the ability to adjust the money supply in response to evolving economic conditions, fixed-supply systems sacrifice macroeconomic stability. They create vulnerability to deflationary pressures, hinder economic growth, and reduce the effectiveness of monetary policy as a tool for smoothing business cycles.

Monetary systems with a fixed nominal supply fundamentally undermine the capacity of central banks to conduct effective stabilization policy. Removing the elasticity of the monetary base constrains adjustment mechanisms essential for maintaining price stability and supporting sustainable growth. Both theoretical models and empirical evidence demonstrate that fixed-supply regimes are ill-suited to the complexities of modern economies and tend to amplify volatility rather than mitigate it.

This article first analyzes the theoretical implications of a fixed monetary base using an overlapping generations model, illustrating why fixed supply cripples monetary policy and exacerbates downturns. It then presents expert consensus and empirical data overwhelmingly rejecting fixed supply regimes. Finally, it critically examines Milton Friedman’s claim that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon,” revealing the multifaceted nature of inflation dynamics.

At the conclusion, it will be clear that even the chairman of the Federal Reserve can be an idiot.

Fixed Supply in Theory: Overlapping Generations Model

We now demonstrate rigorously why monetary systems with a fixed supply, such as those based on gold or Bitcoin, are structurally incapable of delivering macroeconomic stability. The argument is formalized using a canonical overlapping generations (OLG) model.

Time is discrete and indexed by t = 0, 1, 2, … . Each generation lives for two periods. In the first period of life, individuals work, earn income, consume, and save. In the second period, they retire and consume out of their savings. In the third period, they “die”. There is no bequest motive and no intergenerational altruism. Generations overlap such that each period features both young and old agents.

Agents seek to smooth consumption across their two-period lives. Let cty denote consumption when young in period t, and ct+1o denote consumption when old in period t + 1. Preferences are represented by a strictly increasing, strictly concave utility function u(⋅). The subjective discount factor 0 < 𝛽 < 1 reflects time preference. Lifetime utility is given by

Agents receive an exogenous endowment yt in their youth and nothing when old. They must therefore save during the first period in order to consume in the second. The only savings vehicle is fiat money. There is no capital, debt, or other asset market.

Money has no intrinsic value but is accepted as a medium of exchange. Let Mt+1 denote the nominal quantity of money held by the young in period t. Let Pt denote the price level in period t, so real money balances are given by mt = Mt/Pt. Real balances determine the purchasing power of money.

Each agent faces two budget constraints. When young:

This condition states that total expenditures, consisting of consumption and savings in the form of money, cannot exceed current income. When old:

This reflects the fact that the agent consumes entirely out of the money carried over from the previous period, valued at the future price level.

The agent chooses cty, ct+1o, and Mt+1 to maximize lifetime utility subject to these constraints. Formally:

subject to

This defines a standard two-period consumption-savings problem in which money is the only means of intertemporal transfer. The complication arises from the fact that the future purchasing power of money depends on the equilibrium price level, which is not known with certainty at the time of decision-making.

Define the Lagrangian:

Taking derivatives with respect to each choice variable yields the first-order conditions.

With respect to cty:

With respect to ct+1o:

With respect to Mt+1:

Combining these yields the Euler condition:

This ensures optimal intertemporal allocation of consumption.

In equilibrium, the young demand all the money available for their future consumption. If we assume a fixed nominal money supply Mt+1 = M̅, then:

Substituting into the Euler equation:

This pins down cty as a function of the expected future price level. However, the level of M̅ is exogenous and unresponsive to changes in preferences, endowments, or shocks. Therefore, the real allocation must adjust entirely via changes in Pt and Pt+1, creating unnecessary volatility.

To see why this is inefficient, consider the social planner’s solution. The planner chooses {cty, ct+1o} to maximize:

subject to the resource constraint:

In period t, the old consume from what the young saved in t − 1, so let cto = Mt / Pt. Then:

Substitute into the planner’s problem to find the optimal money supply Mt (or equivalently, optimal mt = Mt / Pt) that achieves the efficient allocation.

The planner’s optimal condition is:

This differs from the earlier market condition unless

which is not guaranteed in a fixed-money system, and generally will not hold due to fluctuations in money demand.

Thus, the planner’s condition can only be satisfied if the real value of money adjusts so that both consumption levels match the efficient allocation. This requires that the nominal money supply be endogenously adjusted, since otherwise the real balance mt becomes a residual determined by unpredictable price changes.

Therefore, we conclude that for the decentralized equilibrium to replicate the planner’s efficient allocation, the money supply Mt must be flexible. It must adjust to accommodate changes in real money demand and ensure smooth consumption paths. Fixing the nominal supply Mt = M̅ guarantees deviations from efficiency unless the economy is perfectly static, which is implausible.

In summary, any regime that fixes the nominal money supply, whether it is a gold standard or a crypto-backed currency like Bitcoin, imposes a structural constraint that prevents the price level and real balances from adjusting efficiently. The mathematical solution to this inefficiency is simple and unavoidable: monetary flexibility. A central bank must have the ability to adjust the money supply in response to shocks. Without it, the economy is condemned to suboptimal allocations and unnecessary volatility.

The Empirical Case Against Fixed Supply Regimes

Theoretical clarity is essential, but economic policy must also be supported by empirical evidence. The belief that monetary systems with a fixed nominal supply could outperform discretionary regimes is not only indefensible in theory, but also deeply contradicted by real-world data.

I present three converging lines of evidence: expert consensus, long-run inflation data, and the instability of gold and Bitcoin as nominal anchors.

Expert Consensus: The Gold Standard Reflects Economic Ignorance

The Initiative on Global Markets at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business conducts regular surveys of leading academic economists. These experts represent a range of ideological perspectives but share deep macroeconomic training and professional independence.

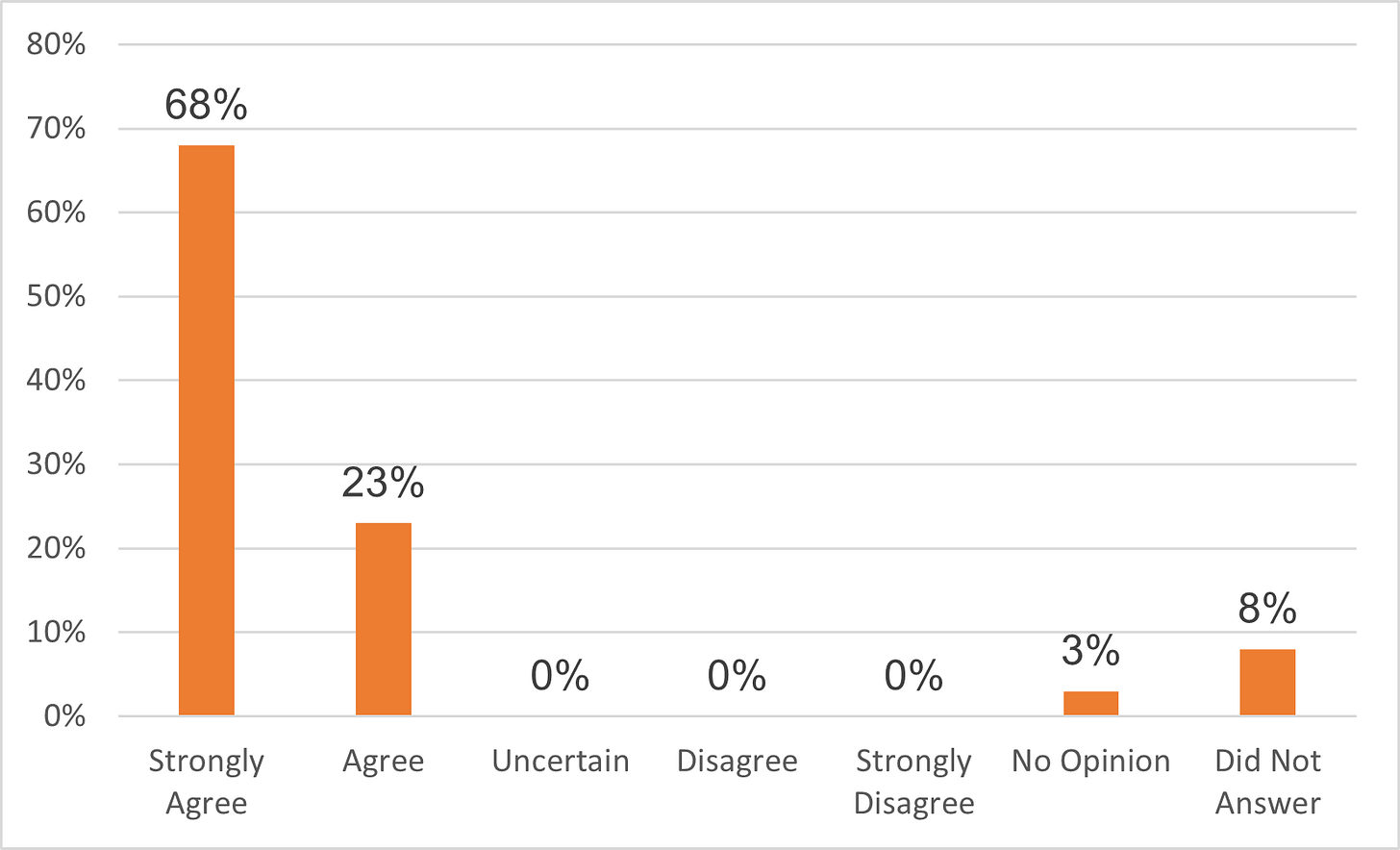

In one such survey (Clark Center, 2012), economists were asked:

Question A: If the U.S. replaced its discretionary monetary policy regime with a gold standard, defining a “dollar” as a specific number of ounces of gold, the price-stability and employment outcomes would be better for the average American.

The responses were:

Among those who answered, not a single economist supported the statement. This degree of unanimity is virtually unheard of in macroeconomics and indicates a complete professional rejection of the idea.

Question B: There are many factors besides U.S. inflation risk that influence the current dollar price of gold.

The responses were:

This second result highlights the central flaw of gold as a nominal anchor: its price reflects a wide array of non-monetary influences, including global demand shocks, commodity market cycles, and geopolitical uncertainty. Bitcoin, often treated as the digital equivalent of gold, suffers from this flaw to an even greater extent due to its speculative nature.

Inflation Stability Results from Discretion, Not Rigidity

Monetarists have long repeated Friedman’s claim that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” While it is true that persistent inflation requires monetary accommodation, this statement overlooks how the structure of monetary regimes, specifically their rigidity or flexibility, influences inflation volatility. Furthermore, it fails to acknowledge the stabilizing effects that discretion and institutional learning have contributed to modern macroeconomic policy.

The historical record is unambiguous: price stability has emerged not from fixed-supply regimes, but from monetary frameworks that allow for flexible, adaptive responses to economic conditions.

The chart below presents the 3-year moving average of consumer price inflation in the United States over the past 250 years, segmented by monetary regime:

During the period governed by the bimetallic and gold standards, inflation was extraordinarily volatile. Fluctuations of ±10 percent were common, and some shocks exceeded ±20 percent. These were not random or idiosyncratic anomalies. Rather, they were the predictable result of a system in which the money supply could not adjust to real shocks, financial frictions, or technological changes. Since monetary quantities were tied to the extraction and circulation of metals, the economy had no recourse when demand contracted or velocity changed.

By contrast, after the collapse of Bretton Woods and the transition to a floating exchange rate regime, inflation volatility declined sharply. Following the disinflationary policy response under Volcker in the early 1980s, the United States entered a prolonged period of low and stable inflation. Central banks adopted forward-looking targets, inflation expectations became anchored, and policymakers developed tools that allowed them to counteract demand shocks without triggering price instability.

This long-run pattern provides decisive evidence against fixed-supply currencies. The regimes built on metal convertibility consistently failed to stabilize prices, and they were prone to both inflationary spikes and prolonged deflations. On the other hand, discretionary monetary policy —when guided by institutional credibility and macroeconomic insight —delivered outcomes that fixed systems could not replicate.

What the historical data shows is not merely a correlation, but a structural incompatibility between monetary rigidity and macroeconomic stability. Flexible money, supported by well-designed institutions, is a necessary condition for the kind of sustained price behavior that modern economies require.

Fixed-Supply Assets Are Inherently Volatile, Procyclical, and Deflationary

Gold and Bitcoin are often praised by their proponents for their fixed supply, which is believed to impose discipline on governments and prevent inflation. However, this rigidity does not stabilize an economy. Rather, it introduces a form of volatility that is both structurally procyclical and deeply damaging during economic downturns. The very feature that is marketed as a virtue—unchanging supply—is, in practice, a macroeconomic liability.

Unlike fiat currencies managed by central banks, the price of gold is shaped by forces that are entirely exogenous to domestic monetary conditions. It is influenced by global commodity cycles, mining output, industrial demand, and speculative capital flows. These determinants bear no consistent relationship to domestic output gaps or inflationary pressures. Bitcoin, despite its algorithmic scarcity and programmable issuance schedule, exhibits even more extreme volatility. Its price dynamics are driven by retail speculation, leverage, and sentiment shocks, none of which reflect the informational needs of a monetary anchor.

Because these assets have a fixed supply, they cannot respond to changes in money demand. This inability becomes especially destructive during recessions, when precautionary motives lead households and firms to hold more cash. If the nominal money supply cannot expand in response, then the adjustment must occur through falling prices. The result is deflation.

Deflation is not the benign opposite of inflation. It imposes real costs across several dimensions. First, it discourages current consumption and investment, since agents expect lower prices in the future. This intertemporal substitution suppresses aggregate demand. Second, it increases the real burden of nominal debt. Households, firms, and governments all find it harder to meet fixed obligations when the price level falls, which can lead to a wave of defaults, deleveraging, and financial instability. Third, deflation disrupts labor markets. Because nominal wages tend to be downwardly rigid, falling prices increase real wages unintentionally, which reduces hiring and leads to involuntary unemployment.

These dynamics were made explicit by Irving Fisher in his debt-deflation theory, which explained how deflation and over-indebtedness interacted to deepen the Great Depression. Under the gold standard, the Federal Reserve was unable to expand the monetary base to accommodate the collapsing velocity of money. The result was a catastrophic contraction in output and employment that was not reversed until the United States abandoned gold.

Bitcoin’s monetary design inherits the same flaw. Its supply is predetermined and unresponsive to shifts in demand. As a consequence, any nominal shock must be absorbed entirely through variations in output or prices. In practical terms, this means that under a Bitcoin standard, the economy would experience severe volatility and persistent deflation whenever demand contracted, even temporarily.

Central banks today target low but positive inflation, typically around 2 percent, not because they are indifferent to price stability, but because they understand that a small, stable rate of inflation serves multiple macroeconomic functions simultaneously. First, it provides a cushion against deflation. By maintaining a positive price-level drift, central banks reduce the likelihood that the economy will fall into a deflationary trap, which, as discussed earlier, can paralyze demand, increase real debt burdens, and exacerbate downturns.

Second, a positive inflation target enhances monetary policy effectiveness by preserving room for real interest rate adjustments. Nominal interest rates cannot fall below zero without incurring substantial distortions, and when inflation is near zero, this constraint severely limits the ability of central banks to respond to recessions. A 2 percent inflation target allows real interest rates to fall into negative territory when needed, facilitating recovery through lower borrowing costs and investment incentives.

Third, and perhaps most crucially, inflation targeting anchors expectations. When households, firms, and financial markets believe that inflation will remain near the central bank's target, wage and price-setting behavior becomes more predictable and stable. This coordination mechanism reduces the volatility of inflation itself and allows the central bank to exert greater control over real variables without inducing large swings in inflation expectations. In this way, inflation targeting is not merely reactive — it is preemptive, stabilizing the economy by shaping forward-looking behavior.

Fourth, moderate inflation supports the functioning of nominal contracts, particularly in labor and credit markets. Because wages and many prices are sticky in nominal terms, a mild rate of inflation allows real adjustments to occur without requiring explicit nominal cuts. This flexibility smooths resource reallocation, reduces the incidence of costly renegotiations, and supports employment during transitions.

None of these stabilizing functions are possible under a fixed-supply regime. With no capacity to accommodate shifts in money demand, absorb shocks, or influence expectations, a gold or Bitcoin-based system lacks the fundamental tools required for monetary management. What appears at first glance to be a safeguard against mismanagement is, in reality, a denial of the very instruments through which stability is achieved.

Conclusion

Calls for a return to the gold standard, or for the adoption of Bitcoin as a monetary base, reflect a fundamental misunderstanding of how modern economies function. The appeal lies in simplicity: a fixed supply seems to promise price stability and insulation from political interference. However, as we have shown, this simplicity comes at an extraordinary cost.

In theory, fixed money supplies are incompatible with macroeconomic stability. In a dynamic economy, the demand for money fluctuates continually, and without the capacity to adjust supply accordingly, the system cannot maintain equilibrium. The result is either persistent inflation or deflation, depending on the alignment of supply and demand. Neither condition can be corrected without monetary flexibility.

Empirically, the historical record is unambiguous. As demonstrated, fixed-supply regimes have delivered greater price volatility, more frequent and severe recessions, and slower recoveries than fiat systems with flexible monetary policy. The myth that gold or Bitcoin ensures long-run stability collapses under both theoretical scrutiny and observed economic outcomes.

More revealing still is the behavior of those who once supported such systems. Even central bankers who previously advocated for gold, such as Alan Greenspan, abandoned these views when faced with the realities of macroeconomic management. The lesson is clear: monetary elasticity is not a design choice, it is a necessary condition for economic resilience. A fixed-supply system cannot accommodate changes in money demand, respond to financial crises, or stabilize inflation expectations. It is precisely to address these needs that modern central banks exist.

A functioning monetary system must be able to absorb shocks, support aggregate demand, and safeguard credit and payment structures. Gold and Bitcoin accomplish none of these tasks. Their fixed supply mechanisms not only prevent effective stabilization but actively propagate instability. They do not offer discipline; they institutionalize dysfunction.

At this point, the reader should understand why moderate inflation is not merely tolerable, but essential. It creates space for real interest rate adjustments, reduces the risk of deflationary spirals, and enables smoother wage and price dynamics in the presence of nominal rigidities. Inflation targeting is not a compromise — it is a solution crafted from a century of empirical insight and theoretical development.

Understanding these mechanisms is more than an academic exercise. It is a prerequisite for informed debate about monetary design. Having followed the logic and evidence laid out in this article, the reader may now feel justified in doing what some might consider necessary: calling Alan Greenspan, former chairman of the Federal Reserve, an idiot.