Politicians love playing economist—and why wouldn't they? There are no consequences for being wrong! They ignore the basics, dismiss the experts, and push policies that inevitably fail. Price controls create shortages? Failure to adjust artificially low interest rates causes spiraling inflation? Who cares! The campaign ads write themselves.

Because let's be honest: Most politicians don't want to create prosperity—they want to create the illusion of helping while securing votes (or, in dictatorships, maintaining the illusion of control while preserving power). If the economy crashes after the election? Perfect. They'll just blame "greedy corporations" or "market failures" or, for strongmen, "foreign saboteurs" or "western agents" and promise to fix it next term. Housing becomes unaffordable? Just cap prices! Wages too low? Mandate higher ones! Potatoes too expensive? Why not outlaw inflation entirely?

So why don’t we use this opportunity to prove politicians wrong? To show that economic illiteracy is the one issue every party agrees on—that no matter left, right, or authoritarian, bad ideas metastasize the moment someone trades textbooks for talking points.

Positive vs. Normative

Let’s first address positive economics and normative economics.

Positive economics is objective and descriptive. It deals with what is—measuring wealth distribution in the USA, analyzing international trade patterns, or documenting economic behavior based on empirical evidence.

Normative economics is prescriptive. It argues what ought to be—determining optimal tax rates, proposing deficit-reduction strategies, or re-evaluating the Maastricht criteria for better outcomes.

This article focuses on normative economics. Specifically, how mainstream economic thought—rooted in historical evidence, theoretical rigor, and statistical analysis—prescribes solutions to policy problems. When politicians ignore these lessons, the results are predictable: inefficiency, unintended consequences, and avoidable crises.

Price Ceilings

A price ceiling is a government-imposed maximum price on a good or service (e.g., rent control, gas price caps). Modern examples abound Germany’s Left Party Die Linke and Vienna’s Greens demanding rent-control "price brakes" or Belarus’s Lukashenko "banning inflation."

Sounds nice in theory, right? Who doesn’t want things to be cheaper?

But here’s the thing: economics doesn’t really care what sounds nice. When you cap prices below what the market would naturally set, bad stuff happens.

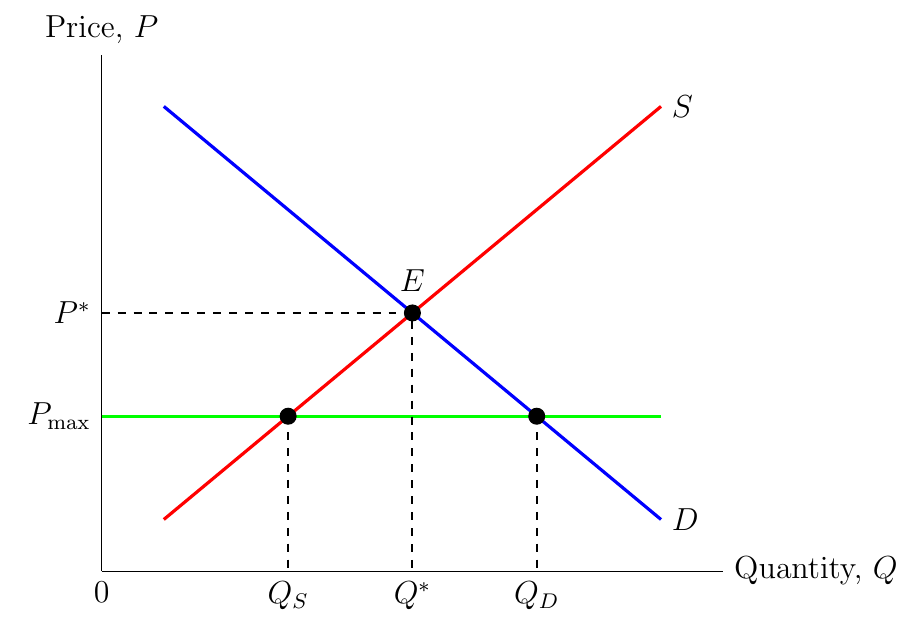

Here’s the supply and demand graph of a price ceiling:

The demand curve slopes downward, reflecting the Law of Demand: For normal goods, when prices rise, quantity demanded falls, and vice versa.

The supply curve slopes upward: As prices increase, producers are willing to supply greater quantities of goods or services.

Where these curves intersect, we find the market equilibrium. At this point quantity supplied exactly equals quantity demanded. There is neither excess supply nor excess demand and the equilibrium price P* and quantity Q* represent the market-clearing values that balance buyer and seller interests.

Now, let’s introduce the price ceiling:

When a binding price ceiling is set below the equilibrium price P* in a competitive market, the quantity demanded exceeds the quantity supplied:

This creates a shortage, disrupting the market equilibrium. When the price ceiling prevents supply and demand from balancing, mutually beneficial trades vanish—resulting in deadweight loss, the textbook definition of inefficiency.

While the shortage and deadweight loss are immediately visible in supply-demand graphs, price ceilings trigger deeper distortions that ripple through economies.

First, they systematically degrade product quality - when profits are artificially constrained, producers inevitably cut corners on maintenance, materials, or service. Rent-controlled apartments famously deteriorate as landlords lose incentive to invest in upkeep.

Second, they breed corruption through black markets, where goods inevitably flow to those willing to pay under-the-table premiums rather than those who need them most.

Third, they misallocate resources by discouraging new supply - why build new housing when rent controls make it unprofitable? This creates permanent scarcity rather than solving it.

Fourth, they impose hidden transaction costs through non-price rationing like waiting lists, lottery systems, or favoritism that waste time and create frustration.

Finally, they distort complementary markets - for instance, rent control leads to higher prices for uncontrolled housing options and furniture storage as secondary effects. These dynamics explain why economists across the ideological spectrum consistently warn against price ceilings, regardless of their political appeal. The visible shortage is just the tip of the iceberg.

So why do some politicians like price ceilings?

Simple: they’re political theater. Price ceilings look like bold action to "help people" (lower rents! cheaper gas!) without requiring messy solutions like actually fixing supply. When shortages inevitably follow, politicians blame everyone and everything but the policy itself.

If you want to see how rent-controls do not work look at the “Berlin freeze”:

The policy was designed in a quite outdated fashion, making use of stringent elements of—for good reasons—rarely used first-generation rent control policies. The rent freeze itself was short-lived, yet the resulting shrinking supply of units for rent is likely to have long-lasting adverse consequences for renters in Berlin.

Hahn et. al. (2024)

Remember: Price ceilings are political tools, not economic tools.

Price Floors and Minimum Wages

A price floor sets a government-mandated minimum price for a good or service, with minimum wage laws being the most prominent example. When set above the equilibrium wage, the effects mirror—but invert—those of price ceilings.

The immediate effect is a surplus—quantity supplied exceeds quantity demanded.

In labor markets, this manifests as unemployment. Employers cannot afford to hire as many workers at the artificially high wage. For goods like crops, it leads to wasteful overproduction (remember the EU's famous butter mountains and wine lakes), with excess supply either rotting in storage or being destroyed—all while consumers face higher prices.

Beyond the visible surplus, price floors distort incentives. Workers who might have accepted lower wages for valuable experience are shut out entirely. Small businesses, already operating on thin margins, may cut hours, automate, or close altogether. In agriculture, guaranteed prices encourage overplanting, depleting resources without regard for actual demand.

Perhaps most perversely, these policies often harm the very groups they claim to protect. Minimum wages, while well-intentioned, disproportionately affect young and low-skilled workers, pricing them out of entry-level jobs. Agricultural supports favor large producers over small farmers, entrenching inefficiency.

The math is simple: by artificially raising the price above what buyers are willing to pay, you inevitably get more sellers chasing fewer buyers. The market’s ability to balance supply and demand breaks down—and the unintended consequences are rarely what policymakers promise.

Yet solutions exist that work with markets rather than against them. Instead of rigid price floors, economists advocate targeted wage subsidies that boost worker pay through tax credits (like the EITC), preserving hiring incentives. Others propose regional minimum wages tied to local living costs, avoiding a one-size-fits-all shock. For long-term gains, skills-based premiums could reward productivity growth, while employer tax relief for training programs helps workers climb the wage ladder naturally. These approaches share a key insight: helping workers doesn’t require breaking the market—just smarter policy design.

The catch? They lack the political theater of a headline-grabbing wage mandate. Real progress rarely fits on a bumper sticker.

Interest Rates

I’ve already written two Substack articles on what happens if politicians get control over managing interest rates and the central bank:

The Federal Reserve vs. The White House

The Federal Reserve was established in 1913 as a response to the financial panics that had plagued the U.S. economy, most notably the crisis of 1907. Its structure—a blend of public oversight and regional private banks—reflected a compromise between those who feared centralized power and those who recognized the need for a lender of last resort. While i…

No, Inflation Does Not Mean Cutting Interest Rates.

Today, Chair Powell had to explicitly state that President Trump’s tariffs will create “higher inflation and slower growth”. The fact that the Fed Chairman had to explain basic economics to the mightiest man on Earth and his supporters shows that even the smallest amount of economic literacy is

To keep it short: Most central banks, like the Federal Reserve or European Central Bank, are independent from politics to prevent short-term political pressures from distorting long-term economic stability. This shields monetary policy from election cycles and populist demands, ensuring decisions are based on economic fundamentals rather than political convenience.

Want an example? How about we let the data speak for itself:

This chart shows how the Turkish Lira has collapsed against the US Dollar over the past 5 years. In 2020, 1 US dollar bought about 7 Lira. Today, it buys nearly 39 Lira - a staggering 462% increase. The steepest drop happened around 2023 when Turkey's government, against all economic advice, forced the central bank to slash interest rates despite raging inflation. This political interference shattered confidence in the Lira, causing its value to plummet. Essentially, the chart tells a cautionary tale: when governments override independent economic policy, currencies can crash rapidly, eroding people's savings and purchasing power. The Lira's collapse made imports more expensive and fueled Turkey's inflation crisis, directly hitting ordinary citizens' wallets.

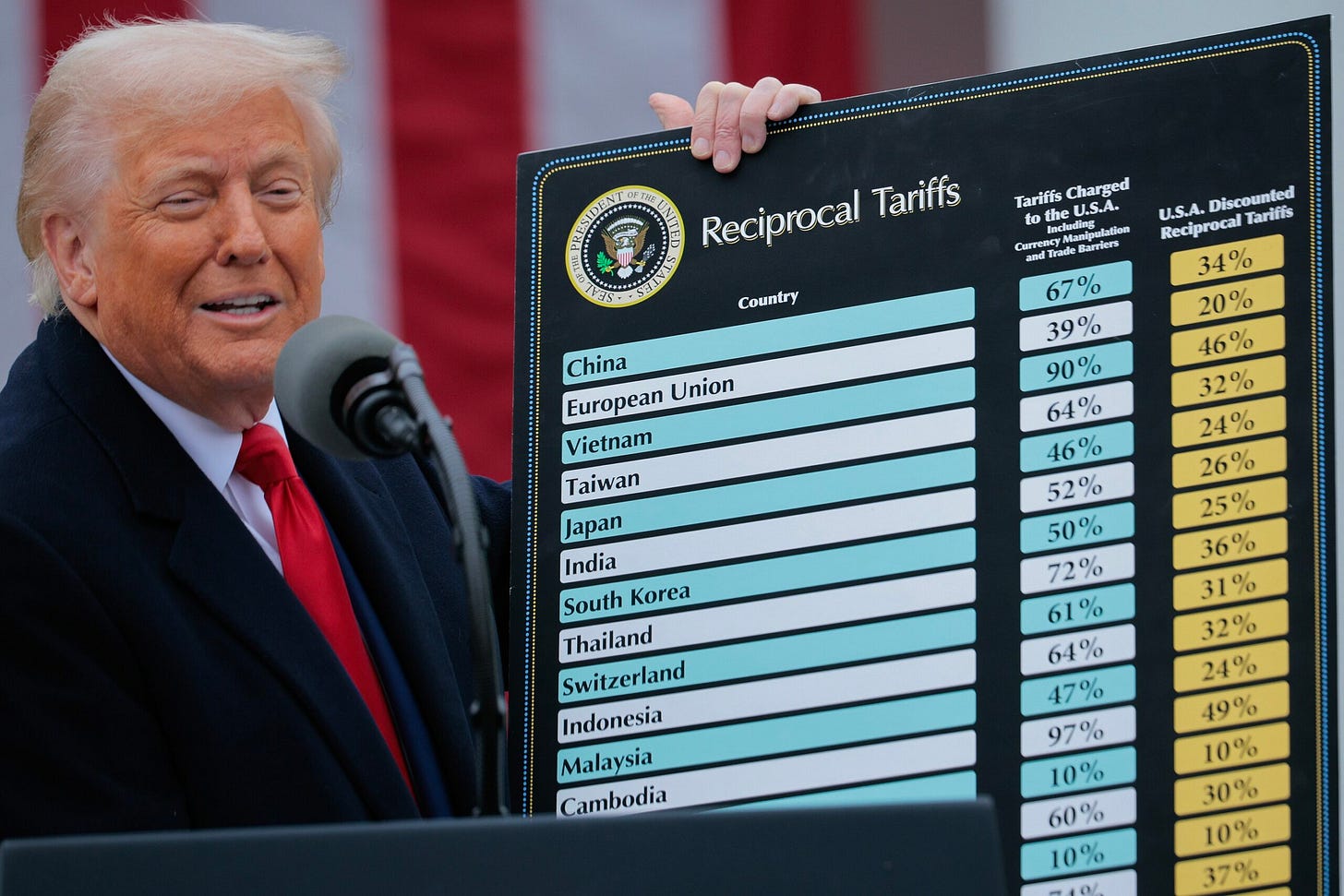

Tariffs

Tariffs are taxes on imports, designed to shield domestic industries from foreign competition. While some politicians sell them as "protecting jobs," they ultimately function as regressive consumer taxes—raising prices for households while fostering inefficiency. Protected industries face less pressure to innovate, while downstream sectors (like manufacturing) pay more for inputs. Retaliatory tariffs compound the damage, shrinking export markets.

Historical examples—from the Smoot-Hawley tariffs worsening the Great Depression to recent U.S.-China trade wars—show they create more losers than winners.

You can’t make a country richer by artificially making it poorer at trade!

Conclusion

Economic principles don’t bend to political will—they break. Politicians may win applause for "fixing" prices, or low interest rates, or by somehow making a country richer through tariffs (???) but the market always delivers the bill: shortages, surpluses, and suffering for the very people these policies claim to help.

This tragic pattern brings to mind what Alan Blinder, 15th Vice Chair of the Federal Reserve, termed "Murphy’s Law of Economic Policy":

"Economists have the least influence on policy where they know the most and are most agreed; they have the most influence on policy where they know the least and disagree most vehemently."

The solution isn’t grandstanding, but humility—policies that work with markets, not against them. Until we heed the consensus of economics over the theatrics of politics, we’ll keep paying for the same lessons in vain.

References

Hahn, A. M., Kholodilin, K. A., Waltl, S. R., & Fongoni, M. (2024). Forward to the past: Short-term effects of the rent freeze in Berlin. Management Science, 70(3), 1901-1923.

Great piece, wasn't expecting for it