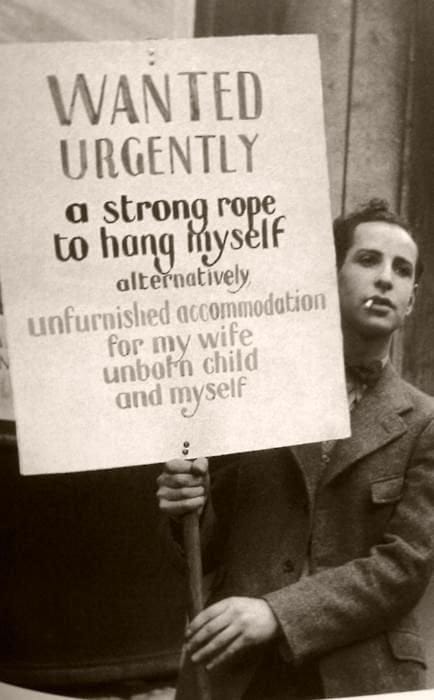

A man in 1932 suffering during the Great Depression.

In 1776, as revolutions reshaped the world, Adam Smith quietly published The Wealth of Nations—a book that would become the bible of free-market capitalism. Smith, the father of modern economics, argued that markets function best when left alone. His "invisible hand" theory claimed that individuals pursuing self-interest would unintentionally benefit society: supply would meet demand, prices would adjust, and economies would self-correct. Governments, he warned, should practice laissez-faire (French for "let do")—or risk distorting the natural order.

For over 150 years, this logic ruled. Then came the Great Depression.

Factories sat idle while workers starved. Banks collapsed while savings evaporated. The invisible hand, it seemed, had let go. Classical economists insisted the crisis would pass—that wages and prices just needed time to fall until recovery sparked. But as the 1930s dragged on, patience became a luxury millions couldn’t afford.

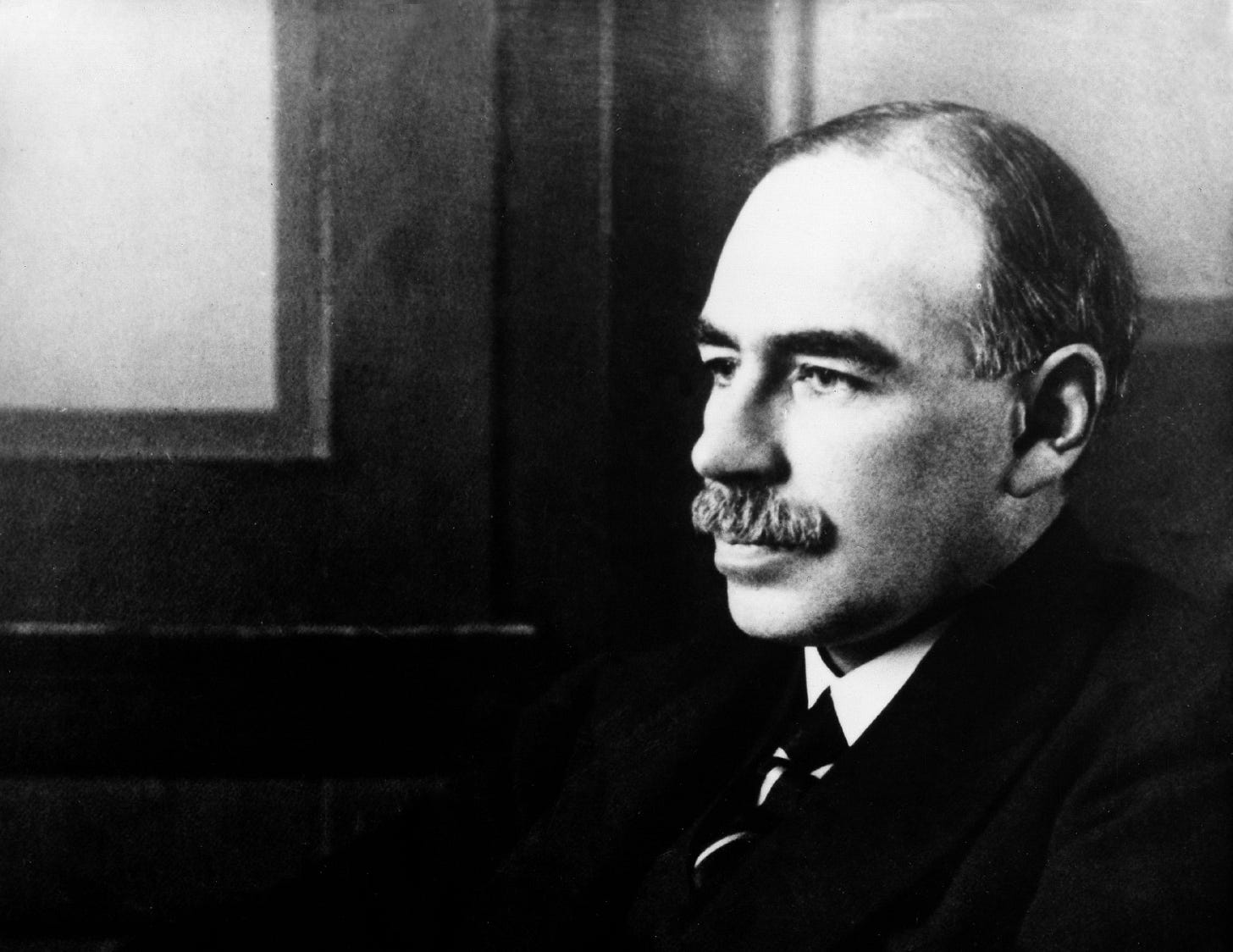

Into this chaos stepped John Maynard Keynes, a British economist, originally trained in mathematics, who declared: What if Smith was wrong?

What if markets, left unchecked, could fail catastrophically—and stay failed? Keynes saw the Depression not as a temporary imbalance but as a collapse of demand: consumers were too poor to spend, businesses too scared to invest, and the economy trapped in a vicious cycle. His solution was considered radical: governments must step in—not as permanent managers, but as emergency spenders, creating jobs and reviving demand when the private sector couldn’t.

Keynes argued that the economy needed a push—a stimulus—to escape this downward spiral.

This was the birth of demand-side economics: the idea that sometimes, the economy needs more than invisible hands. Alternatively, people use the term Keynesian economics to refer to the man who started it all

In the following paragraphs, we'll unpack the core principles of Keynesian economics, examining how this influential school of thought diverges from classical and neoclassical approaches. We'll explore the evolution of Keynesian theory through its various modern interpretations, and most importantly, investigate why Keynes' ideas continue to shape economic policy in our 21st century world - from stimulus packages to crisis management to monetary policy.

What is Keynesianism?

At its core, Keynesian economics argues that aggregate demand—the total spending by consumers, businesses, and government—drives economic growth. Unlike classical economists, who believed markets naturally self-correct, John Maynard Keynes showed that during recessions, fear and falling incomes can trap an economy in prolonged stagnation. His solution? Active fiscal policy: governments should spend when the private sector won’t, boosting demand to revive growth and employment.

The foundation of Keynesian analysis can be summarized in a basic macroeconomic equation:

Where Y is national income, C is consumption, I is investment, G is government spending and (X—M) is the difference between exports and imports (net exports).

Keynes’ idea was that if C and I collapse (e.g., in a recession), G can compensate to stabilize Y.

This simple equation reveals Keynes’ revolutionary insight: markets don’t always self-heal. When households and businesses cut spending (consumption and investment decrease), the economy contracts—and without intervention, the slump can persist. By increasing government spending (e.g., through infrastructure projects or unemployment benefits), governments inject demand directly, creating a ripple effect: workers earn wages, spend more, and businesses regain confidence to invest.

Keynesianism’s legacy lies in its pragmatism. It doesn’t reject markets but corrects their failures. From FDR’s New Deal to 2008 bank bailouts (marking the “Keynesian Resurgence”) and COVID-19 stimulus checks, Keynes’ ideas remain the go-to toolkit for crises. Critics argue about debt risks or "crowding out" private investment, but history’s lesson is clear: when demand collapses, waiting for recovery isn’t policy—it’s surrender.

Keynesianism vs. Classical and Neoclassical Economics

"[…] Ricardo conquered England as completely as the Holy Inquisition conquered Spain"

Keynes, J. M. (1936). The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money

Keynesian economics broke sharply from classical thought by rejecting the notion that markets naturally self-correct to full employment. Classical economists like Adam Smith and David Ricardo believed in Say’s Law—the notion that "supply creates its own demand," meaning recessions were temporary “glitches”. They argued that falling wages and prices would eventually restore equilibrium without government intervention. Keynes, however, demonstrated that during a downturn, falling incomes could lead to a vicious cycle of reduced spending, layoffs, and further demand collapse, trapping economies in prolonged slumps.

Though more mathematically rigorous, neoclassical economics still upheld the classical faith in market self-correction. Neoclassicists focused on individual optimization—households maximizing utility and firms maximizing profits—assuming flexible prices and wages would always clear markets. Keynes countered that in the real world, prices and wages were "sticky" (i.e., slow to adjust), and panics could lead to hoarding rather than rational spending. Where neoclassicists saw recessions as brief deviations, Keynes saw them as potential spirals requiring deliberate fiscal action.

Most critically, classical and neoclassical economics treated savings as always beneficial, channeling funds into productive investment. Keynes showed that excessive saving during a crisis could worsen demand shortages, dubbing this the "paradox of thrift." His framework shifted the focus from long-run equilibrium to short-run crises—where psychology, uncertainty, and policy choices mattered far more than abstract models suggested.

This focus on short-term crises is best captured in Keynes’ famous remark:

“But this long run is a misleading guide to current affairs. In the long run we are all dead.”

Keynes, J. M. (1923). A Tract on Monetary Reform

Varieties of Keynesianism

While all Keynesians agree on the primacy of aggregate demand and the need for policy intervention, the school has fractured into distinct branches since Keynes' era.

Neo-Keynesian Economics, supported by economists like Paul Samuelson and Franco Modigliani formalized Keynesian macroeconomics within general equilibrium theory, introducing the Phillips Curve trade-off between inflation and unemployment. They maintained Keynes' emphasis on demand shocks but incorporated optimizing behavior and gradual price adjustment through wage rigidities.

Post-Keynesian Economics, attributed to economists like Hyman Minsky or Wynne Godley rejected equilibrium analysis entirely, focusing instead on fundamental uncertainty, endogenous money creation by banks, and financial instability. Minsky's Financial Instability Hypothesis formalized how economies transition from stability to crisis through debt accumulation patterns.

New Keynesian Economics, supported by Gregory Mankiw, Olivier Blanchard or Joseph Stiglitz, developed microeconomic foundations for nominal rigidities using imperfect competition, menu costs, and efficiency wage theory. Unlike Neo-Keynesians, they derived macroeconomic implications from explicit firm-level optimization under constraints, while preserving Keynesian policy conclusions about active stabilization.

New Keynesianism

New Keynesian economics has emerged as the predominant framework in contemporary macroeconomic analysis, particularly among central banks and policy institutions. Its ascendancy stems from successfully integrating Keynesian demand-side insights with rigorous microeconomic foundations - a synthesis that earlier Keynesian variants lacked.

The framework's widespread adoption reflects three key strengths:

First, its explicit modeling of nominal rigidities through empirically-grounded mechanisms like menu costs, staggered price contracts (Calvo pricing), and efficiency wages provides plausible explanations for short-run monetary non-neutrality.

Second, by incorporating rational expectations and optimization behavior, it maintains consistency with modern economic methodology while still generating Keynesian policy implications.

Third, its dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) formulations allow for quantitative policy evaluation through formal econometric estimation.

This analytical rigor has made New Keynesian models the standard tool for inflation targeting regimes and stabilization policy analysis. The Federal Reserve, European Central Bank, and International Monetary Fund all employ New Keynesian DSGE models in their forecasting and policy work. Take the New York Fed's DSGE model that forecasts GDP growth, core Personal Consumption Expenditures inflation, and the real natural rate of interest as example.

While debates continue about specific calibration issues and the models' performance during crises, the framework's ability to combine theoretical coherence with practical policy relevance ensures its central position in macroeconomic research and applied policy analysis today.

From its revolutionary response to the Great Depression to its formalization in modern New Keynesian models, Keynesian economics has proven to be more than a crisis toolkit—it is a fundamental lens for understanding market economies. While debates continue about the precise role of fiscal activism or the limits of monetary policy, Keynes' central insight remains unchallenged: economies lack natural guarantees of full employment, and demand matters.

The widespread adoption of New Keynesian frameworks by institutions like the Fed confirms this legacy. Even as new challenges emerge—from secular stagnation to climate transition—the core Keynesian principle endures: when private demand falters, purposeful policy can stabilize and restore growth. Markets are powerful, but not infallible; Keynesian economics reminds us that sometimes, the invisible hand needs a steadying guide.

Ultimately, Keynesianism is neither radical nor obsolete—it is a pragmatic response to economic reality. As long as economies face crises, its lessons will remain indispensable.