The Science of Scarcity, The Logic of Choice

The indispensable framework for constrained existence.

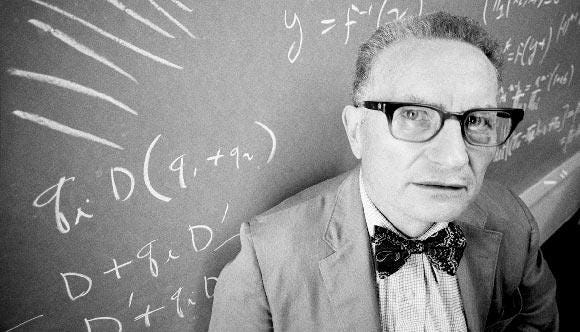

“By 1935 economics entered into a mathematical epoch. It became easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a non-mathematical genius to enter into the pantheon of original theorists.”

Paul Samuelson (1976)

"Economics isn't a real science."

It’s a lazy critique echoing through comment sections and faculty lounges — dismissing the discipline as mere ideology, a playground of untestable theories and politicized guesswork.

They’re wrong. Fundamentally.

The field's scientific intent is explicit in its foundational definition, articulated a century ago by British economist Lionel Robbins:

Economics is the science which studies human behaviour as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses.

Lionel Robbins (1932)

This foundation demands more than observation: it forges inevitable truths through logical deduction, subjects them to brutal empirical testing, and operates through a razor-edged system of reasoning designed for constrained choice.

This article dismantles the myths. Economics is a science — because its critics profoundly misunderstand what rigorous analysis looks like when applied to the universal condition of scarcity.

Foundational Laws

Critics sneer, "Where are economics’ universal laws?" Their error? Confusing the science itself with its messy application in political economy. When politicians twist policy to serve votes, not truths, outcomes distort — but that doesn’t invalidate the underlying logic. Science begins with axioms. As Richard Thaler observed:

"In fact, economists often compare their field to physics; like physics, economics builds from a few core premises."

Richard Thaler (2015) Misbehaving: The making of behavioral economics.

From scarcity’s bedrock, irrefutable laws emerge — not through polling, but inescapable deduction.

Want an example?

Let pi denote the price of good i, xi its quantity consumed, and m the agent’s income. Then:

This is a budget constraint, commonly used in microeconomics. It states that an agent cannot consume more than their income, whether that be money or an equivalent monetary commodity, allows them to.

"Isn’t this obvious?" Exactly. That’s the point. This is economics’ conservation of energy.

Now consider econometrics' cornerstone: The Law of Large Numbers.

Let X1, X2, … , Xn be independent, identically distributed random variables with mean µ. Then:

As data grows, sample averages converge to true theoretical expectations. This isn’t economics — it’s mathematical law. Yet it enables economics to become empirical science, as this math allows us to approximate unobservable population truths through sample averages.

The Statistical Crucible: Where Theory Meets Bloodsport

The budget constraint is law. The LLN is truth. But science demands more than deduction — it requires theories to survive contact with data. Enter econometrics: the statistical battlefield where elegant theories either emerge victorious or die screaming.

Consider how this unfolds. Economic theory might declare, based on axioms of rationality and scarcity, that individuals smooth consumption over their lifetimes — spending modestly during peak earning years to sustain themselves in retirement. The Permanent Income Hypothesis makes this precise. But does it actually describe human behavior?

Enter the econometrician. Armed with the Law of Large Numbers — they design tests. They might analyze decades of household surveys, tracking income and spending across tens of thousands of real people. Modern techniques like Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) take this further. Imagine randomly assigning a basic income supplement to one group while withholding it from a comparable control group. As data accumulates, the Law of Large Numbers ensures any difference in spending patterns between the groups isn’t random noise, but evidence of causal behavior. This isn’t speculation; it’s how Nobel-winning work by Banerjee and Duflo exposed the real impacts of anti-poverty programs.

Or take contentious policy debates. When politicians argue whether raising the minimum wage destroys jobs, econometrics cuts through the rhetoric using Difference-in-Differences. Researchers compare employment trends in regions that raised wages against statistically similar regions that didn’t — before and after the policy change. The Law of Large Numbers validates whether the comparison groups are truly comparable, isolating the policy’s effect from broader economic shifts.

And when hidden biases threaten to corrupt conclusions — like asking whether education causes higher wages, or if smarter people simply pursue more education — econometrics deploys Instrumental Variables. Clever researchers might exploit historical quirks, like compulsory schooling laws that forced some populations to stay in school longer for reasons unrelated to ambition. If these "instruments" truly affect education but not wages directly, the Law of Large Numbers helps verify their validity, teasing out causation from correlation.

Critics dismiss this as glorified number-crunching. They’re profoundly mistaken. Curve-fitting can’t isolate causality; RCTs, Difference-in-Differences, and Instrumental Variables do precisely that, grounded in the mathematical certainty of convergence. This is economics’ empirical backbone: subjecting deductive truths to statistical trial by fire. No ideology survives a well-executed RCT. No political narrative can repeal the Law of Large Numbers.

The Unseen Logic: Economics as the Algebra of Life

Beyond equations and data lies economics' most profound power: a reasoning system that deciphers all human action under constraint. This is not mere theory — it is the hidden scaffolding of reality itself. Utility maximization and opportunity cost are not financial terms; they are universal laws of behavior that manifest wherever scarcity forces trade-offs.

Consider a parent at 3 a.m., torn between sleep and a crying child. Here, economics operates in its purest form. The parent doesn't calculate dollars — they weigh the marginal utility of 30 minutes of rest against the crushing emotional cost of their baby's distress. The opportunity cost of sleep is the child's suffering; the cost of soothing is tomorrow's exhaustion. This is optimization in raw humanity: a visceral cost-benefit analysis where the currency is well-being and the budget constraint is time.

Or witness nature's unforgiving classroom. A bird defending its territory doesn't need a bank account — it faces an energy budget. Every second spent fighting a rival carries an opportunity cost in calories burned and predation risk. The bird implicitly calculates: does the marginal survival benefit of this patch of ground outweigh the marginal energy expenditure? When the cost exceeds the benefit, it retreats. Diminishing returns govern its wings.

In an overwhelmed hospital ward, a doctor allocates the last ventilator. No money changes hands, but economic logic prevails. Each decision carries a brutal opportunity cost: assigning the machine to Patient A means Patient B dies. The doctor — consciously or not — maximizes utility where utility is measured in lives saved. They prioritize the patient with reversible conditions, the young over the old, because the marginal gain in life-years is highest. This is not cruelty; it is scarcity's grim arithmetic.

Even now, as you read these words, your mind runs an economic algorithm. Your limited attention is the ultimate non-renewable resource. You subconsciously weigh the marginal utility of each sentence against the dopamine lure of social media, the pull of unfinished work, the fatigue behind your eyes. When the cost of concentration exceeds the perceived benefit, you will stop — a decision as economic as any stock trade.

Critics call this reductionist. They miss the revelation: economics doesn't reduce humanity — it reveals the structure of choice itself. That student choosing between a party and studying? They're solving a utility function where grades trade against social connection. That activist volunteering countless hours? They're investing in a cause where emotional returns outweigh leisure costs. That artist agonizing over brushstrokes? They're optimizing aesthetic impact under time constraints.

Conclusion

Scarcity is the unyielding condition of existence. From this crucible, economics emerges not as ideology or guesswork, but as a science of choice — rigorous, tested, and universal.

It begins with the clarity of mathematics: axioms distilled into truths as immutable as the laws governing falling bodies or converging waves. These are not opinions etched in ink, but principles carved into the logic of scarcity itself.

It advances through the forge of evidence: theories subjected to data’s unforgiving light, where statistical fire separates insight from illusion. What survives is knowledge refined — not by rhetoric, but by reality’s verdict.

And it reveals itself everywhere: in the quiet calculus of a parent soothing a child at midnight, the split-second triage of a doctor under siege, the instinctive retreat of a bird preserving energy. Economics is the silent choreographer of survival.

To deny its science is to deny that choices have structure, that trade-offs obey logic, that human ingenuity thrives within constraints. Mathematics gave economics precision; empiricism gave it proof; scarcity gave it purpose.

In the end, economics is the study of how we navigate a bounded world — and in that navigation, we discover not just efficiency, but meaning.

The equations map the terrain. The science illuminates the path.

> “But science demands more than deduction — it requires theories to survive contact with data. Enter econometrics: the statistical battlefield where elegant theories either emerge victorious or die screaming.”

Are there good examples of empirical work overturning theory? It seems that often, when the result is unexpected, the takeaway is that the empirics are flawed rather than the theory incorrect.

The minimum wage could be an example, but many will argue the original DiD papers were quite flawed. The monopsony power explanation is also heavily contested anyways.

Since you didn't define income I'm assuming you use it as commonly understood: Money (or some alternative) earned through work or investment.

Now take the following sections from your article, on fundamental laws and budget constraints:

"This is a budget constraint, commonly used in microeconomics. It states that an agent cannot consume more than their income, whether that be money or an equivalent monetary commodity, allows them to."

And

"The budget constraint is law."

This is exactly the kind of statements that make people say that economics is not a real science. How can you write an article saying that economics is super scientific, and all of that, and then begin your 'foundational laws' with an obviously false statement. As an economist, have you never heard of a loan? (or a gift, or theft, but lets focus on loans). A loan is something which allows you to consume more than your income, ergo your foundational law is wrong. And not wrong as Newton's theory on gravity, which describes observable events in the world correctly but is probably wrong about the underlying mechanisms due to the complexity of how it all works, but wrong as in this is not what happens in the real world and it therefore cannot be observed.

Loans are actually foundational to our entire monetary & financial system, therefore need to be integrated in any economic analysis from start.

And yes, simple loans, in theory need to be paid back: However, again, empirical observation will tell you this doesn't always happen. Some people go bankrupt, some people die before paying it back, some loans are not paid back ever and earn interest in perpetuity, some are rolled over, some can be exchanged for stock, etc. That's why people like Fisher and Minsky, to name just the obvious ones, were so interested in the financial system, and debt, and all of that, because it is foundational to, and therefore fundamentally affects, how the economy functions.