When critics attack economic models for being "unrealistic," they reveal a profound misunderstanding about the nature of scientific modeling. They're making the same mistake as dismissing a road map because it doesn't show every pothole, traffic light, and roadside diner. The map works precisely because it omits these details to highlight what matters: how to get from point A to point B.

A model that perfectly depicted reality would be reality itself, completely useless for analysis or prediction. The power of economic models lies precisely in their strategic departure from realism. This isn't a flaw to apologize for. It's the essence of scientific progress.

Friedman's Revolutionary Defense

Milton Friedman demolished this naive criticism with a brilliant insight that revolutionized economic methodology. In his 1953 essay "The Methodology of Positive Economics," Friedman argued that judging theories by the realism of their assumptions misses the point entirely. What matters is predictive accuracy and explanatory power.

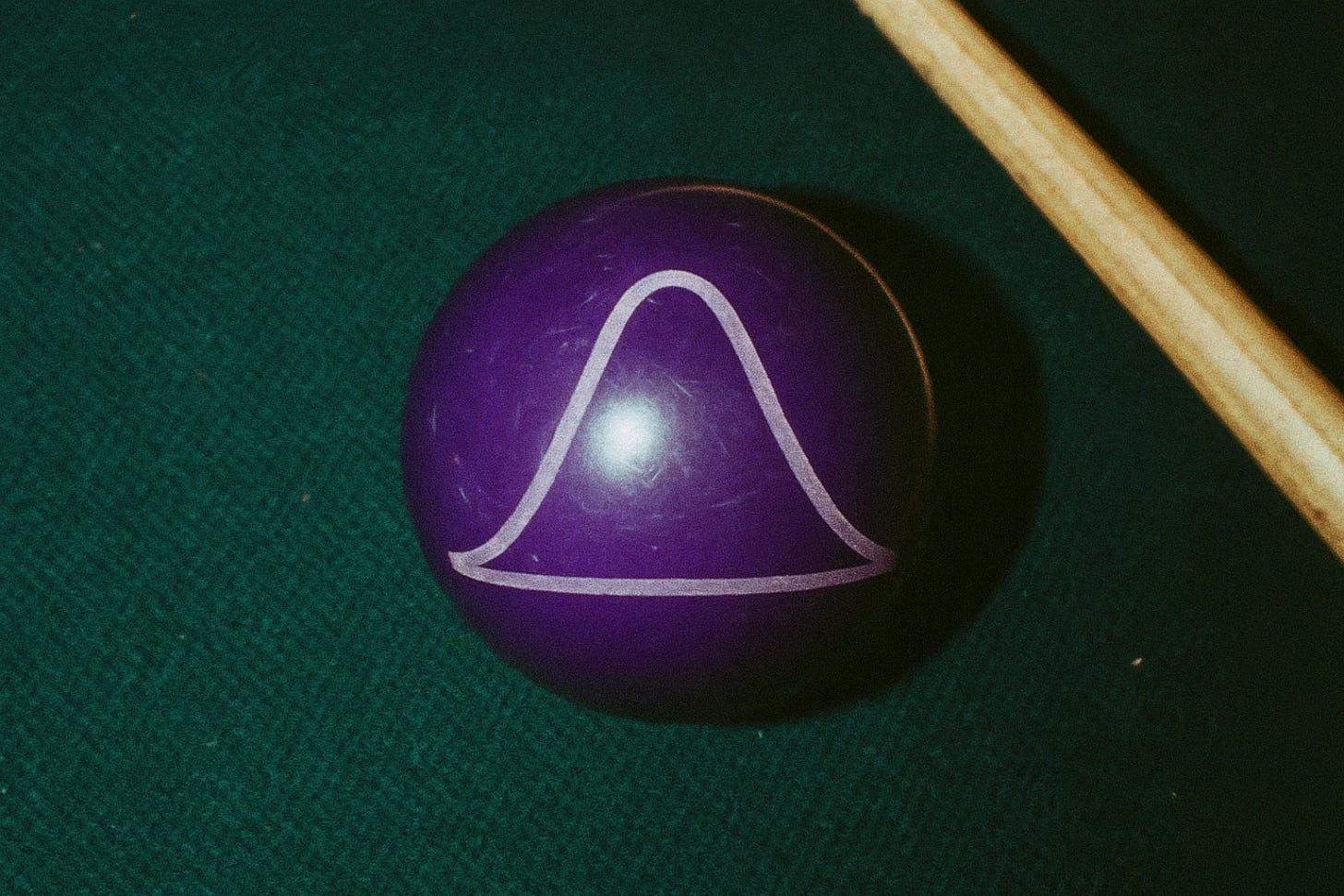

Consider Friedman's famous billiards player analogy. Imagine watching a skilled player sink shot after shot with impressive precision. If you tried to explain their success, you might describe how they calculate angles of incidence and reflection, account for ball spin and momentum transfer, and adjust for table friction using complex physics equations.

But here's the thing: the player probably never studied physics. They can't solve differential equations or calculate coefficients of friction. Yet they play as if they had a PhD in applied mathematics.

This is Friedman's "as if" defense. People don't need to actually perform complex calculations if the results look the same as if they had. The billiards player succeeds through practice, intuition, and trial and error. But for prediction purposes, we can model their behavior as if they were human calculators.

The same logic applies throughout economics. Business owners don't literally use calculus to maximize profits, but they behave as if they do because market forces eliminate those who consistently misprice their products. Consumers don't solve optimization problems when shopping, but they act as if they do because experience teaches them to get maximum value for their money.

The beauty of this defense is that it separates mechanism from outcome. We don't need to believe people are superhuman calculators. We just need to recognize that various pressures push behavior toward the same outcomes that perfect calculation would produce.

The Lucas Revolution: When Realistic Models Failed

Robert Lucas delivered the next devastating blow to naive realism in the 1970s. Mainstream macroeconomic models, which seemed "realistic" because they incorporated observed historical relationships, broke down spectacularly when policies changed.

These traditional models treated behavioral relationships as fixed. They observed that historically, high unemployment correlated with low inflation. Policymakers believed they could exploit this trade-off: accept more inflation to get lower unemployment.

But when governments systematically tried this in the 1970s, they got both high unemployment and high inflation simultaneously. The "realistic" models failed completely.

Lucas diagnosed the fatal flaw: these models assumed people's behavior would remain unchanged when policies changed. But people adapt when the rules change. If government announces systematic inflation to reduce unemployment, people start expecting inflation. Workers demand higher wages. Businesses raise prices preemptively. The policy defeats itself by changing the very relationships the model assumed would stay fixed.

Lucas's solution was radically more unrealistic: populate models with infinitely-lived representative agents solving dynamic optimization problems:

No real person behaves like this mathematical construct. The representative agent lives forever, has perfect knowledge, and solves complex equations every period.

Yet these impossibly unrealistic models proved far more reliable for policy analysis. Why? Because they derived behavior from deeper structural parameters that don't change when policies change. Surface relationships could shift, but the underlying optimization problem remained stable.

The Lucas Critique revealed a profound truth: models that appear realistic by matching observed correlations can be less useful for policy questions than models built on unrealistic but stable foundations.

Why Your Coffee Shop Proves the Point

Consider your neighborhood coffee shop. Economic theory says the owner sets prices where marginal revenue equals marginal cost:

The owner probably couldn't define "marginal cost." They've never seen this equation. They just know from experience that pricing requires delicate balance.

Price too high, customers walk to Starbucks. Price too low, you lose money on every cup. Through trial and error, they find their sweet spot.

The model captures this messy process by assuming perfect mathematical calculation. The assumption is obviously false, but the prediction is remarkably accurate. Coffee shops worldwide end up pricing close to what the model predicts, not because owners are mathematical geniuses, but because those who price poorly don't survive.

The market acts like a ruthless teacher. Shops that price too high lose customers. Those that price too low go bankrupt. Survivors stumble onto strategies that approximate profit maximization through whatever combination of intuition, experience, and luck.

The coffee shop owner behaves as if they solved the optimization problem, even though they've never heard of optimization. Market pressure creates this "as if" behavior by rewarding success and punishing failure.

Supply and Demand: Strategic Simplification

The basic supply and demand model makes spectacularly wrong assumptions:

All products are perfectly identical

Everyone has complete information about all prices

No search costs or transportation delays

Prices adjust instantly to clear markets

Walk into any marketplace and you'll see these assumptions violated constantly. Yet this "unrealistic" model correctly predicts fundamental patterns everywhere: higher prices reduce quantity demanded, lower prices increase it, cost changes affect market prices, demand shifts move prices in predictable directions.

The model works because it isolates the most fundamental force: people substitute toward relatively cheaper options and away from expensive ones. Everything else is detail that matters in specific contexts but doesn't change this underlying relationship.

Consider gas stations on the same corner charging nearly identical prices. The model assumes infinite competitors, but even three stations create powerful competitive pressure. If one charges significantly more, customers walk across the street. If one charges less, it attracts lines or runs out quickly.

The stations behave as if they were in perfect competition, even though they're not. The model's unrealistic assumptions capture competitive pressure that drives this behavior.

Rational Expectations: Superhuman Foresight

Perhaps the most unrealistic assumption in modern economics is "rational expectations": people know the true economic model and process information perfectly:

This assumes superhuman cognitive abilities that obviously don't exist. Yet models with this assumption successfully predicted that anticipated monetary policy would have no real effects, that systematic fiscal policy would trigger offsetting private responses, and that currency pegs would face speculative attacks.

The assumption works because markets punish systematic errors. While individuals make mistakes, those who consistently forecast poorly lose money and influence. The profit motive eliminates predictable irrationality, making the "as if" rationality assumption useful for aggregate prediction.

When Behavioral Economics Overcomplicated Things

Behavioral economics attempts to make models more realistic by incorporating psychological insights. This sounds like obvious progress, but it sometimes creates problems. More accurate descriptions of individual psychology can yield less useful predictions about aggregate behavior and muddy policy guidance.

Consider models incorporating present bias, where utility becomes:

with 𝛽 < 1 capturing short-term impatience. This better describes individual choice but complicates welfare analysis. Should policy respect revealed preferences or correct for bias?

Traditional economists often criticized behavioral models not because their psychological insights were wrong, but because the added complexity frequently obscured rather than clarified policy recommendations. Sometimes strategic unrealism preserves analytical clarity needed for practical application.

The fundamental trade-off remains: realism versus tractability. Unrealistic models maintain clarity that enables precise predictions and actionable policy guidance.

The Scientific Method in Economics

Economics follows standard scientific methodology. Physicists model gases as perfectly elastic spheres, ignoring molecular complexity. Chemists use Lewis structures that misrepresent electron distribution. Biologists use population models that ignore individual variation.

These aren't flaws. They're scientific achievements that enable understanding through strategic simplification. Economic models work the same way, succeeding by isolating key relationships while assuming away complicating factors.

Models serve three functions:

Prediction:

Forecasting outcomes under different scenarios

Explanation:

Identifying causal mechanisms

Prescription:

Guiding policy decisions

Unrealistic assumptions often enhance all three by eliminating confounding factors and providing clear benchmarks.

The Art of Strategic Unrealism

The key insight from Friedman, Lucas, and modern methodology is that model selection should be driven by purpose, not surface realism. Different questions require different models. The criterion isn't whether assumptions match reality, but whether the model generates insights unavailable from alternatives or provides better predictions than competing frameworks.

Realism isn't a single dimension. Models can be realistic about some things and unrealistic about others. The art lies in being unrealistic about the right things while capturing what matters for the question at hand.

Conclusion: Embrace the Impossible

Stop apologizing for unrealistic economic models. Celebrate them! The best models in economics are strategically, deliberately, productively unrealistic. They work not despite their departure from reality but because of it.

The question isn't whether assumptions are realistic. It's whether the model helps us understand something important about how the world works. By that standard, many of our most "unrealistic" models are our most successful.

In economics, as in all science, truth emerges not from perfect photography but from strategic abstraction. The model is not reality, and that's exactly why it's useful. The power lies not in perfect reproduction, but in revealing essential relationships through deliberate simplification.

When someone criticizes an economic model for being unrealistic, remember: they've missed the point entirely. The unrealism isn't a bug to be fixed. It's a feature to be celebrated.

I think economics is in the opposite situation: the theory captures very well the relevant elements of market economies, but it is not very useful for forecasting.

I wrote this, that perhaps can be interesting to you:

https://open.substack.com/pub/theseedsofscience/p/prediction-and-control-in-natural?r=biy76&utm_medium=ios

Thanks. Lucid and concise…very concise!